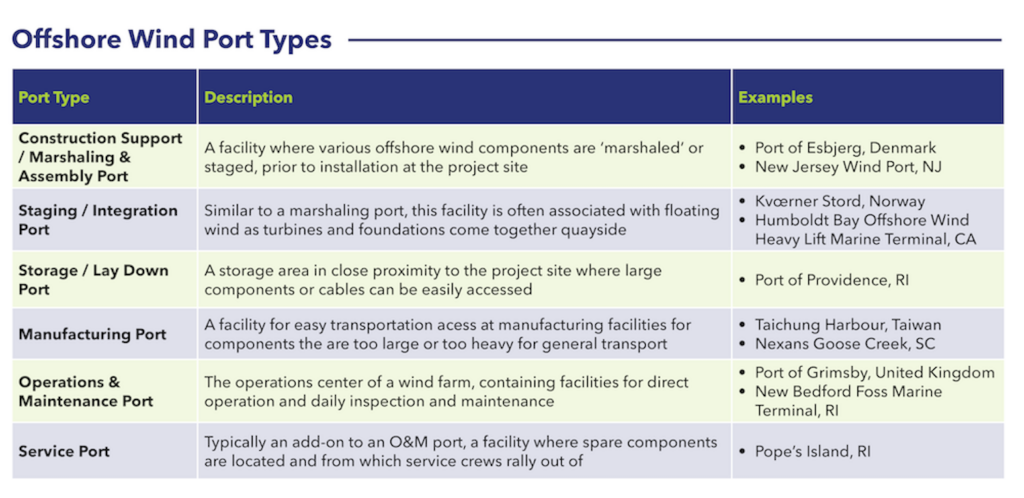

You cannot have offshore wind without ports. This simple fact has already launched $4 billion in new investments into waterfront cities up and down the East Coast, putting thousands of Americans to work building enormous civil infrastructure projects. For decades to come, these towns will serve as bustling operations hubs with vessels and maintenance crews offering communities a new lifeblood of commerce and opportunity. Offshore wind’s U.S. port needs are enormous, and the work completed to date is just a fraction of what the nation will inevitably build to support the new industry.

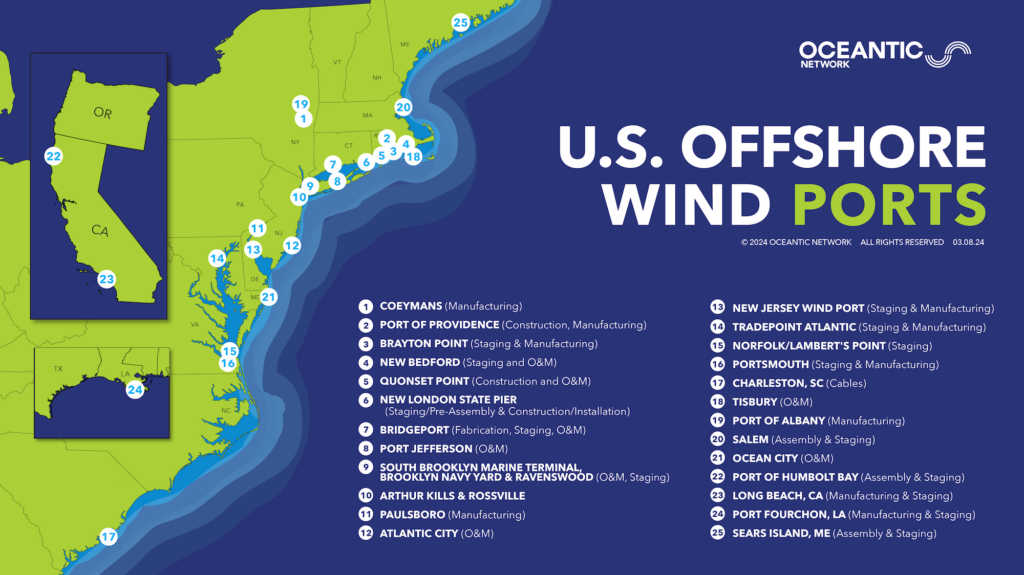

Oceantic Network has identified 25 U.S. ports currently involved in offshore wind or undergoing development to support the industry, with dozens more rumored or planned. These range from $20 million projects, like smaller Crew Transfer Vessel (CTV) operations and maintenance (O&M) ports and modest manufacturing quays, to enormous all-in Marshalling & Assembly plus O&M developments like Equinor’s $861 million South Brooklyn Marine Terminal (SBMT). The Network, using closely tracked data from the U.S. offshore wind market, conservatively estimates that the current public and private investment into offshore wind ports stands at $4.2 billion.

Those projects have put Americans to work in short-term construction jobs and long-term operations activities.

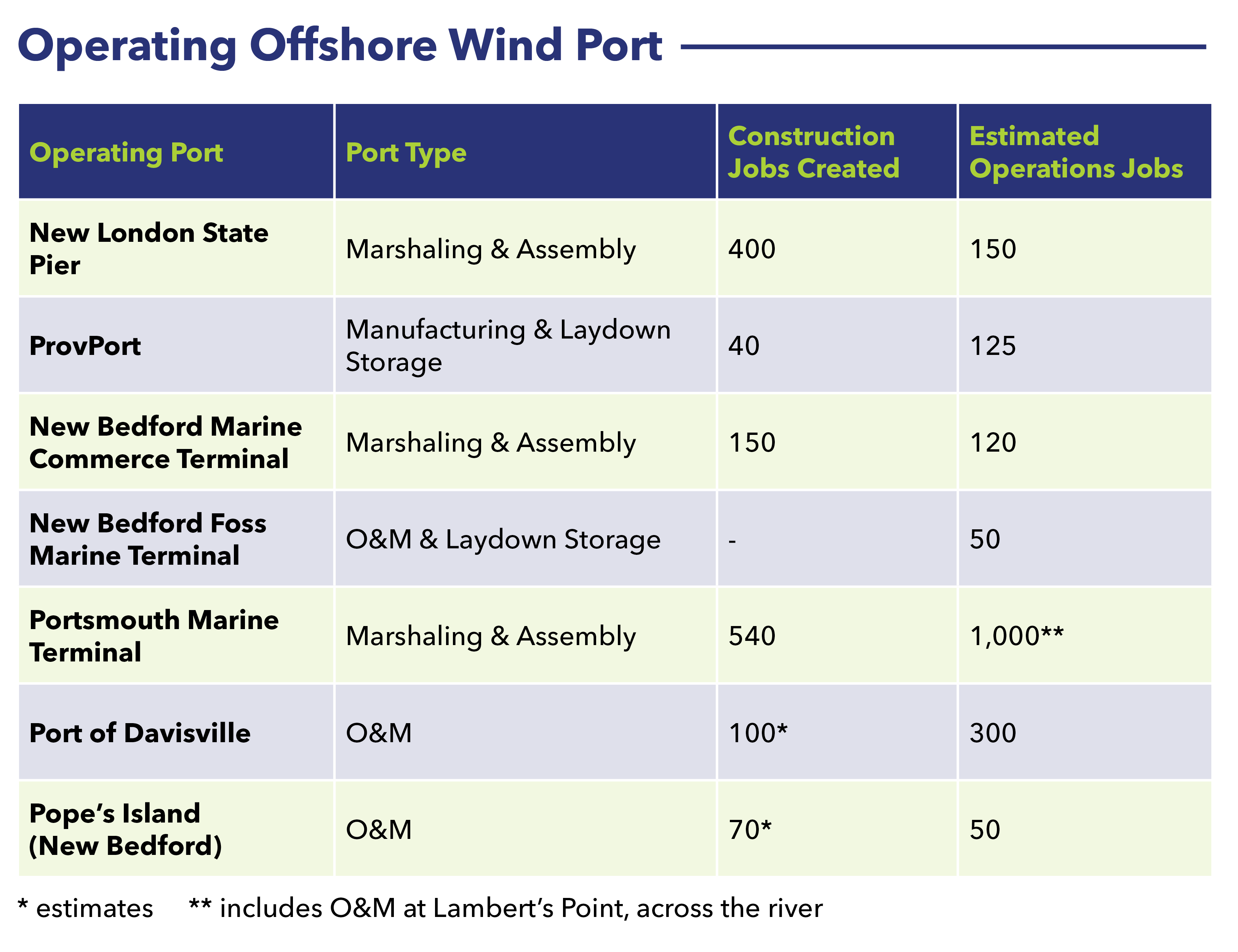

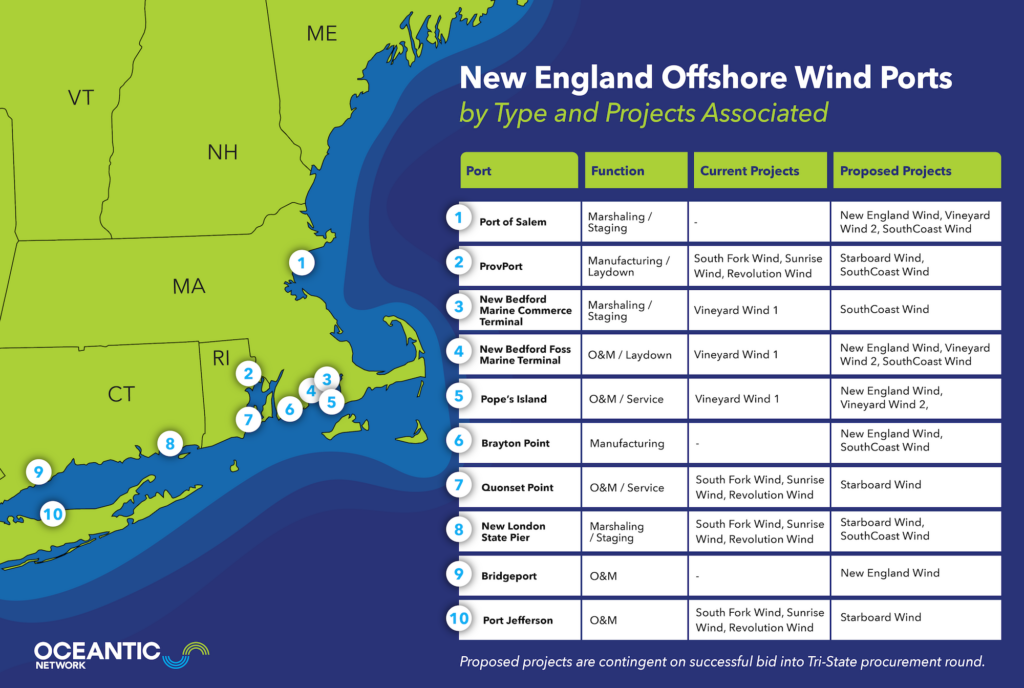

As of July, the U.S. had six currently operating offshore wind ports including New Bedford Commerce Terminal, MA; Foss Marine Terminal in New Bedford, MA; New London State Pier, CT; Port of Providence, RI (ProvPort); Port of Davisville, RI and Portsmouth Marine Terminal, VA. According to public reports, their collective construction has supported at least 1,000 jobs, and their operations will sustain another 400 annually. The nearly completed New Jersey Wind Port has already supported more than 200 jobs, and SBMT’s construction is projected to create 1,000 more in the heart of New York City.

Some ports under development will anchor long-term manufacturing investments. The New Jersey Wind Port, for example, is expected to sustain 1,500 jobs when fully complete, with manufacturing facilities adjacent to long-term Marshalling and Assembly operations activities. Rhode Island is already excelling at attracting these investments. ProvPort has evolved into offering storage, bunkering, and secondary steel manufacturing for two different commercial-scale projects, creating 120 jobs annually for the past 3 years. The Port of Davisville is also planning its future around the long-term operations and maintenance needs of offshore wind. Operator Quonset Development Corp. has so far invested $175 million of a $234.5 million master plan that aims to position the port to service projects for decades to come — whether that be by sea, or by air. Already, the port is playing a key role as a hub for South Fork O&M.

Much of the industry’s early activities are taking place in America’s northeast, home to smaller ports that once beamed with shipping, shipbuilding, and fishing activities. The New London State Pier, originally developed in the late 1800s as a ship-to-rail connection, was largely considered underutilized as of five years ago. Now, public officials are using offshore wind as a catalyst to make major facility upgrades to handle both traditional cargo and renewable energy. As a Marshalling & Assembly port, New London is already supporting the construction of three commercial-scale projects totaling 1,750 MW. The project is a prime example of how strategic investments can revitalize forgotten areas.

Similarly, the New Bedford Foss Marine Terminal, previously a derelict fossil fuel plant, is set to become a major multi-tenant O&M and laydown hub. Salem, MA, once home to an old coal plant, is undergoing a similar transformation to become the Salem Offshore Wind Terminal, another prominent Marshalling & Staging facility. And in Baltimore, MD — where Tradepoint Atlantic now sits where the largest steel mill on the East Coast used to operate — the city will soon feature both foundation and cable manufacturing facilities. These projects will bring hundreds of millions of dollars in manufacturing investment, employ hundreds of new clean energy trades people, and mark a return to the region’s industrial roots.

The economic revitalization of areas such as New Bedford, Salem, and Tradepoint Atlantic highlights how offshore wind supply chain development is driving investment into underutilized infrastructure and creating a platform for new middle-class clean energy jobs.

Ensuring that there is a consistent, long-term stream offshore wind projects utilizing these repurposed sites is equality important. For example, New London and ProvPort are expected to remain continuously busy for at least four years, supporting the construction of South Fork Wind, Revolution Wind, and soon, Sunrise Wind. However after that, the ports may face utilization gaps and potential job reductions due to inconsistent offshore wind project deployment. While, both New London and ProvPort have been listed as preferred locations in new offshore wind project proposals, construction and manufacturing activities for those project will not begin again until later in the decade.

Without consistent offshore wind project demand, existing offshore wind port facility may need to transition again to support other industries, newly trained workers may move to other jobs, and it will become even harder to finance and build the additional port capacity we need to support our national and state-level offshore wind deployment goals.

Port financing is already a major bottleneck in the U.S. offshore wind industry. Last year, the Oceantic Network published, Building a National Network of Offshore Wind Ports, authored by Clean Energy Terminals’ Brian Sabina and the Network’s Ports Working Group. The report highlighted the need for at least 65 new U.S. offshore wind port facilities, requiring at least $36 billion in new investment over the next decade. While these figures may sound substantial, $36 billion is approximately 4-6% of the expected private sector investment in U.S. offshore wind generation projects over the next 35 years. And, without this enabling investment, offshore generation projects can’t be built.

The U.S. offshore wind industry urgently needs more investment into port facilities. Increasing public sector grant funding, at both the state and federal levels, that is specifically targeted to these projects is critical not only to meet deployment timelines and but also attract greater amounts of private sector funding, too. New London, for example, attracted $100 million direct private investment from Ørsted and Eversource after the state’s early commitment of public funds for the project. The Network’s paper highlights other financing support structures states could use to spark private investment, like revenue guarantee, which would help cover debt-service payments if a privately financed port was inactive due factors outside of its control (such as the uneven deployment facing the East Coast ports mentioned above). Such smart financial tools help spread risk between the public and private parties and attract significant attention from traditional infrastructure investors.

The promise of economic development from offshore wind will be realized in our ports. However, it will only be realized with expanded strategic infrastructure investments, the use of new smart financing approaches, continuous project pipelines, and a continued faith in the path forward. Redevelopment in New Bedford has transformed the harbor town into an offshore wind hub. The $300 million invested in New London has sparked a local economic renaissance and is supporting a multi-state supply chain all the way to Texas. The four billion dollars already injected into U.S. offshore wind ports may only be a crumb of what is ultimately needed, but it is already having a tangible impact on American communities along, and far from, the coast.