When the ECO Edison steamed into the Port of Providence earlier this month, it made one thing clear: Offshore wind is a powerhouse of potential for U.S. shipbuilding.

Born in the Louisiana bayou, ECO Edison will serve as a key piece of the multi-decade operations and maintenance supply chain tasked with keeping northeastern wind projects running smoothly. Construction of the $97 million Service Operations Vessel (SOV) took more than two years and put at least 600 Americans to work. The project’s broader supply chain – where everything, from steel and engines to interior paneling and electronics, was sourced – reached 34 states.

The ECO Edison is one of 50+ newbuild and retrofitted vessels announced in response to the more than 12 GW of offshore wind power offtake agreements states have contracted — a fraction of the overall state demand which now surpasses 115 GW, including codified targets and planning goals. Combined, the current vessel orders are bringing at least $1.7 billion into 13 U.S. shipyards across eight states, from the Gulf of Mexico to the Northeast, and even in the Great Lakes.

As the ECO Edison showed, the impact of such projects reaches far beyond a shipyard’s docks. Using collected supplier contract data, the Oceantic Network found these 13 shipyards are sourcing from steel plants in seven states often far from the coast, including Iowa, Ohio, Pennsylvania, and West Virginia. Engines and other major components parts were sourced out of Illinois, Indiana, and Georgia. Just one vessel, the $650 million Wind Turbine Installation Vessel (WTIV) Charybdis being constructed in Brownsville, Texas pulled steel from Alabama, Texas, West Virginia, and North Carolina.

The shipyards themselves are major job creators, often serving as long-term employment hubs in rural communities. Using public data and member interviews, the Oceantic Network found just five shipyards (out of the 13 identified as having worked on offshore wind vessels) have collectively employed more than 2,500 people that helped build offshore wind vessels. Interviews with this growing industry’s demand. Wally Naquin of Edison Chouest said the new orders have helped his community deal with declining opportunities from less oil and gas work. “We don’t have to do any layoffs because of the [offshore] wind industry. Its renewed, not just our shipyard, its renewed southeast Louisiana [because] we [are] keeping people working.”

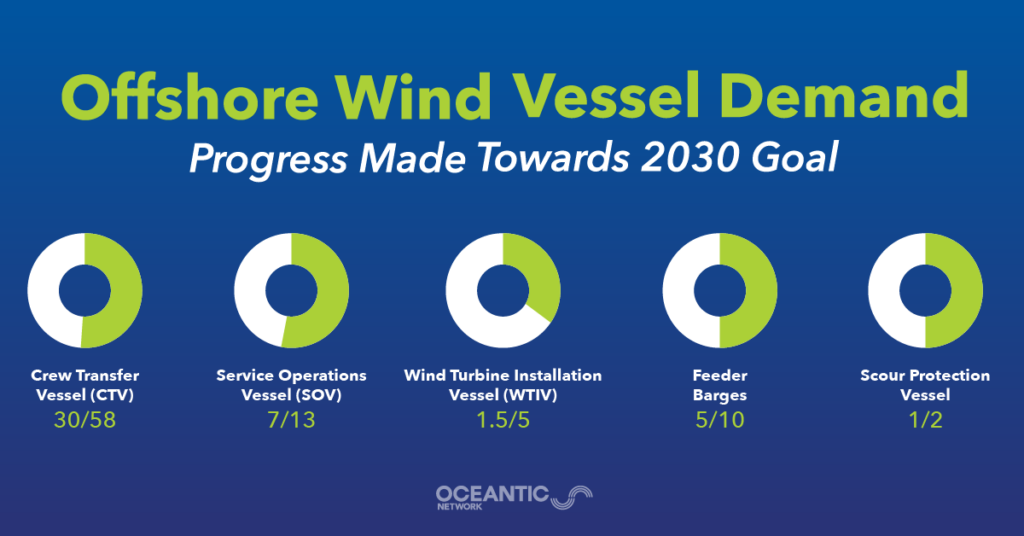

Estimates offer a glimpse into the sheer magnitude of demand for offshore wind shipbuilding. For example, federal researchers determined the industry would require 58 Crew Transfer Vessels (CTVs) under the Biden Administration’s 30 GW of offshore wind energy by 2030 goal. Another estimate from analyst group Intelatus Global Partners finds that total swells to 130 for an 87 GW market. That equals a $1.14 billion opportunity for U.S. yards for just one vessel classification – and the smallest one at that!

CTVs are the workhorses of the offshore wind maritime industry, ferrying technicians on daily trips to and from turbines. As smaller vessels usually tied to individual wind farms, they are the easiest to finance and can be manufactured at many U.S. shipyards. As of today, U.S. yards have launched ten new CTVs, retrofitted three others, and have 17 on order, several of which the Network anticipates launching in the next couple of months. To meet the estimated industry requirements for the 30 GW target, however, would require that fleet to double.

As vessel classifications grow larger, they become harder to finance and fewer yards have the capabilities to build them. For example, SOVs like the ECO Edison can cost upwards of $100 million to construct. These “floating hotels” allow technicians to spend weeks at sea during both installation and maintenance periods. Besides the Eco Edison, two more SOVs are well underway at the Edison Chouest yard in Houma, Louisiana and the Fincanteri Bay Shipbuilding yard in Sturgeon Bay, Wisconsin. Three others have been retrofitted from existing oil and gas assets, with a fourth currently in progress. Federal researchers estimate 13 are needed in total to meet the 30 GW goal, meaning another requirement to double.

Installation vessels have proven the hardest to build in the U.S., and currently only two are under construction: the aforementioned $650 million Charybdis and the $250 million scour protection vessel Acadia, which recently laid its keel in Philadelphia. This vessel classification faces three simultaneous challenges. First, financing a vessel requires several years of contract guarantees; installation vessels go from project to project, and with market fluctuation and the lack of a clear, long-term development pipeline, lining up even a few years of contracts is difficult. Second, certain installation activities do not require the use of U.S.-built vessels, meaning prospective owner-operators will face stiff foreign competition once the vessel is launched. (This has, however, opened the door to new, innovative installation techniques, leading to increased tug and barge construction). Finally, there are a limited number of U.S. yards capable of building a WTIV, which can drive up prices and slow production.

Solving the installation vessel conundrum is one of the most important policy challenges facing the U.S. offshore wind market. Because of their specialized nature, supply is low globally, and demand is only increasing. The loss of an installation vessel can have cascading detrimental impacts on a wind farm’s deployment, even leading to overall project cancellation.

Offshore wind is not alone; similar challenges are facing U.S. shipbuilding across the board including the defense sector, domestic shipping, and other maritime activities. In the years since World War Two, the number of American shipyards capable of handling vessels of 500 feet or more has dwindled from 50 down to just 20 today. Securing the U.S. offshore wind industry requires addressing the entire shipbuilding sector — energy, commercial, and defense — with targeted investments in yard capacity and new financing and insurance mechanisms so that U.S. yards can produce globally competitive offshore wind vessels.